Today, August 29, is the 19th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina and the failure of the New Orleans levee system. It’s an event that residents of New Orleans and the Mississippi gulf coast who experienced it will never forget. There have been essays, memoirs, books, songs, and all kinds of art made from this disaster. Today I’m sharing an essay I wrote that was published in Atticus Review in 2021. There are many more eloquent accounts than this but this is my story. Rather, a piece of it. It was a long time before I could string together coherent thoughts about everything that happened before, during, and after the storm. I thank my friend and beta reader Jamie Etheridge, and Rachel Laverdiere and Lucy Wilde, Atticus CNF Editors at the time, for their help in polishing this piece.

DÉJÀ RÊVÉ IN THE GULF

A dream presented itself two weeks before the storm, for the third time. An overwhelming presence repeated “Get out!” with a palpable feeling of dread and danger, a certainty that the Big One was coming. You know how it is with dreams—you’re filled with a superpower of “knowing” without knowing how or why. According to dream data, déjà rêvé is defined as the recollection of a specific dream on a specific date that comes true.

*

On the Gulf of Mexico, you live with the possibility of hurricanes from June through November. My husband and I had done our share of hurricane evacuations many times. But we always came back in a day or two with everything just fine, except maybe a few shingles off the roof and debris in the yard.

Katrina kicked the ass of the paradigm. She came so fast. We worked feverishly—boarding, hammering, dragging in outdoor furniture and plants, raising indoor furniture on blocks, gathering clothes, files, meds, pet supplies—for a who-knew-how-long evacuation. The car was filled with people and pets, the trunk stuffed with clothes and necessities. We drove away from our home of twenty-seven years about 2 a.m. with the spit dry in our mouths, our hearts pounding. It was an eerie drive. We were all hopped up on adrenaline, yet exhausted at the same time. The radio gave tracking coordinates and played disaster songs like “Rock You Like a Hurricane” and “Riders on the Storm” that didn’t help our anxiety. They sounded like nails dragged down a chalkboard. It felt frivolous for stations to be playing these songs while people were running from potential disaster. As I glanced repeatedly at my nervous pets and mother-in-law in the back seat, apprehension grew like black clouds in my chest, my hand in a white-knuckled grip on the armrest. My mind was its own storm front of worry. Would my house and garden survive? Would the city survive? What would we do if we lost it all?

*

Throughout history, many cultures have believed dreams are a well of spiritual guidance from a divine source giving them a higher knowledge than normal. Ancient Egyptians believed divine revelation could be received through dreams and that people who had vivid, specific dreams were blessed. There is a monument between the paws of the Sphinx describing how Thutmose IV restored it because of a dream that he would be made Pharaoh. Dreams are often a mix of past, present, and a possible future, incorporating bits from our lives and experiences. Did our decision to evacuate out of town instead of vertically or sheltering in place come from divine guidance? Certainly, the dream was on my mind.

*

We arrived at a relative’s house in Mississippi feeling like we’d been run over by a truck. After the storm passed, we stayed glued to a New Orleans radio station for information. People were calling in desperate for news of their loved ones, not knowing if they made it out, or if they were even alive. People called in on their land lines, which still worked, unbelievably. Cell phones were worthless, at first. Later, people trapped in their homes, in attics and on roofs, began calling. I’ll never forget one lone woman calling for help as someone broke into her house. Then pictures of the aftermath started coming in on TV: scenes of destruction, of looting, of the water, the water, always the water—because the levees had broken. Residents were told to stay away, that no one was allowed back into the city and the National Guard would enforce it.

After a couple of days, I was able to go online. Desperate for information about my neighborhood, I found a woman on the Internet who was in contact with friends who hadn’t evacuated and who lived in my section of the city. I was able to find out my neighborhood was not flooded, my home intact waiting for our return. Through her contacts, I began to build a network of locals and friends of locals where I found real boots-on-the-ground information. The “news” coming from MSM consisted of frustrating sensationalized photo-essays. The real news was online in community forums. People helping people.

*

About four weeks later, I rode down to the city with a friend of a friend amid lines of National Guard vehicles and disaster relief trucks. I had expected to see families returning home, not government convoys. As we approached, my heart dropped into my stomach at the unfolding scene. Dried, caked mud was in every street, debris and splintered trees strewn around like Lego pieces abandoned by an enraged child. Building after building was boarded up or in various states of destruction. The iconic Superdome came into view, appearing to be riddled with holes, swaths of the outer material hanging in shards. I thought about the disturbing stories from people who took refuge there and felt a heavy sadness. Multistoried buildings with broken windows like black eyes stared into space. Over it all, smothering heat, eerie silence, a surreal sense of apocalypse. New Orleans had been utterly unprepared for an event that had been predicted for as long as I could remember. It was a city in a coma waiting for life support.

Driving into my neighborhood was a shock, even though some of the streets were clear enough to traverse. The huge old elm tree in our front yard was uprooted, lying across the street and into the neighbor’s yard. More mud and debris everywhere. My beautiful tropical back garden was a tangle of branches, banana trees, roof shingles, roofing nails, splintered wood, and trash of all sorts. It looked like a bomb had exploded.

*

Days passed. The whine of patrolling helicopters and the growl of chainsaws were our only company. Have you ever experienced a day without birdsong? There were no birds. Or traffic noise? There were no buses, no moms driving kids to school, no one going to work. Or a city in total darkness at night? There were no streetlights. All but two homes on our block sat as empty as a politician’s promise. We were under curfew, but it didn’t matter. There was no place to go.

So, I blogged. I coped by writing about beauty, wonder, love—while bubbled in a suspended life. I researched and wrote about local history, about space and astronomy. Armchair visited other countries and cultures. I discovered other local bloggers who were sharing disaster relief information, dispelling wild myths circulating about what was happening, and raining hell on people saying New Orleans shouldn’t be rebuilt. These bloggers were the first writers—grassroots writers—I came to know in real life.

They wrote about the strange lives we were living, the collapse of the city infrastructure, the incompetent response of the government. They wrote about the growing piles of garbage, the stink, the coffin flies, nails in your tires, how to clean out rotting food from freezers and refrigerators or how to duct-tape them closed and haul them to the curb. They wrote about dozens of fires from leaking gas lines, the heroics of the NOFD who worked beyond exhaustion. They wrote about rich men planning to move our beloved football team to another city. They wrote about the lack of healthcare and the growing number of suicides and deaths by stress and grief. They tried to hold insurance companies and politicians accountable, swapped info about blue tarps, Red Cross stations, food lines, medication shortages. They gave me something to hold on to and kept me company in that long dark autumn. Despite the tragedy that spawned this network of bloggers, it was a golden era in the New Orleans online writing community.

*

Dreams can be warnings but also opportunities. Someone dreamed of an invisible superhighway, accessible to all, connecting all, creating community across time and space. In that way, the Internet is like a dream we are all having, a déjà rêvé of time and space and memory.

***

Tomorrow, a flash essay about life after.

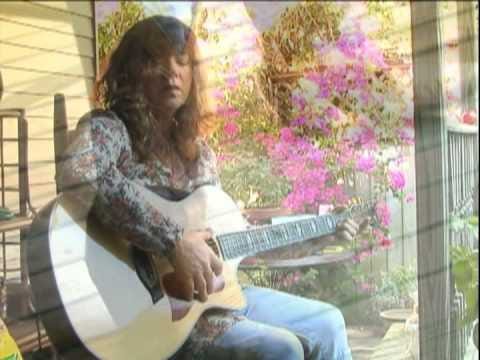

I hope you’ll watch this poignant music video by longtime New Orleans resident Susan Cowsill, “Crescent City Sneaux”. It was written contrasting the rare Christmas snow we had in 2004 with the hurricane in 2005. I got teary-eyed watching & listening again after many years.

I remember when this was first published Charlotte. I loved it then and I love it now. I would say this is eloquent! I haven't had an experience like this and you put me there.

🤞Two more months and we can exhale. But then, this took my breath away. ❤️